News

Largest modelling study of its kind highlights need for joined-up climate and biodiversity policy

News | Apr 2024

The largest modelling study of its kind to date shows an urgent need for policies that better understand the interlinked nature of climate change and biodiversity loss, and their potential impacts on human societies, say scientists at the UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC), who were involved in the research.

Global biodiversity declined by between 2 per cent and 11 per cent during the 20th century due to land-use change alone, according to the large multi-model study published in Science. Projections show climate change could become the main driver of biodiversity decline by the mid-21st century.

The analysis was led by the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU), with contributions from scientists at the UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC). The researchers compared 13 models to assess the impact of land-use change and climate change on four distinct biodiversity metrics, as well as on nine ecosystem services – the benefits nature provides to humans.

Calculating the impact of land-use change on biodiversity

Land-use change is considered the largest driver of biodiversity change by the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). However, scientists are divided over how much biodiversity has changed in past decades. To better answer this question, the researchers ran new land-use models to assess the impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem services over the 20th century, in an important step for biodiversity science, this type of modelling having previously mainly been carried out for climate science.

UNEP-WCMC’s Principal Scientist Dr Samantha Hill ran one of the eight models that were used to calculate four biodiversity metrics (global species richness, local species richness, mean species habitat extent and biodiversity intactness). She used the Projecting Responses of Ecological Diversity in Changing Terrestrial Systems (PREDICTS) database developed by UNEP-WCMC and the Natural History Museum in London. This is one of the world’s largest datasets of biodiversity observations, with data from 3.3 million observations across 25,000 sites collected by researchers around the world. The observations record how species are exposed to differing anthropogenic pressures – allowing researchers to model how biological communities change as a result of human activities.

Dramatic results from modelling climate and land-use change

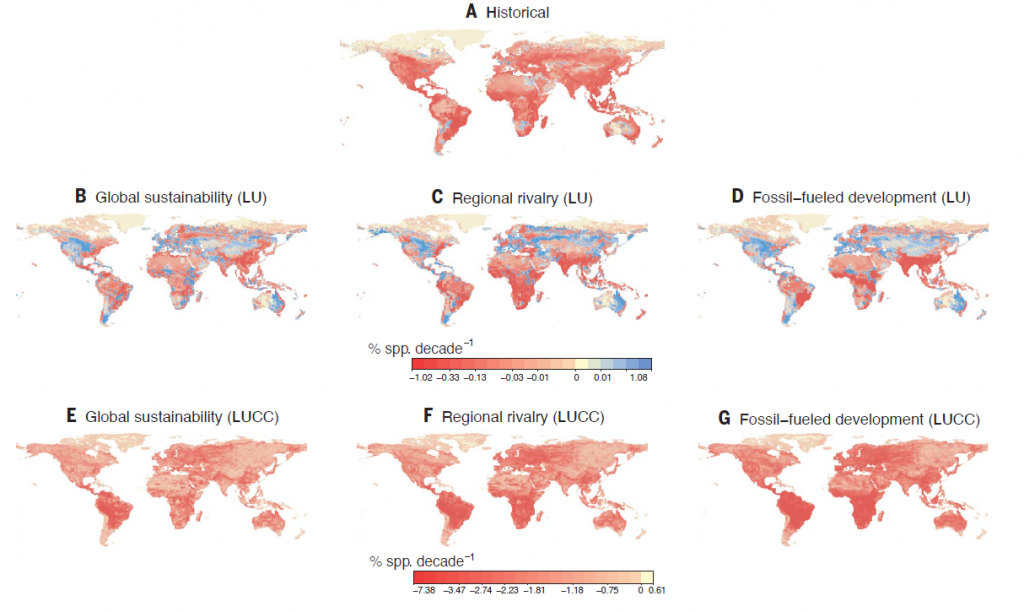

Dr Hill applied the PREDICTS data to three plausible future scenarios: Global Sustainability, Regional Rivalry and Fossil-Fuelled Development, with differing pathways for population growth, socioeconomic development and greenhouse gas emissions. Her work was brought together with the seven other models to examine how biodiversity and ecosystem services might evolve in the future.

For all three scenarios, the impacts of land-use change and climate change combined result in biodiversity loss and accelerated extinctions in all world regions. While the overall downward trend is consistent, there are considerable variations across world regions, scenarios and models.

The findings show that climate change is likely to put additional strain on biodiversity and ecosystem services. While land-use change remains relevant, climate change could become the most important driver of biodiversity loss by mid-century.

Using another set of five models, the researchers also calculated the simultaneous impact of land-use change on ecosystem services. In the past century, they found a massive increase in provisioning ecosystem services, like food and timber production. By contrast, regulating ecosystem services, like pollination, nitrogen retention, or carbon sequestration, moderately declined.

We were shocked by the scale of potential biodiversity loss by 2050 when both climate change and land-use change modelling was used. The results raise really important questions for climate and biodiversity policy around the world and justice, given even under the Global Sustainability scenario, species richness is estimated to drop if further measures are not put in place.

If development progresses in line with the scenarios, countries in northern Africa and the Indian sub-continent will experience greater loss of biodiversity along with many of the regulating services biodiversity brings, making these countries, which are already climate-vulnerable, more exposed to some of worst impacts of climate change. And this is in the most sustainable scenario tested: the loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services is estimated to be both more dramatic and more inequitable by other scenarios.

Dr Samantha Hill, Principal Scientist at UNEP-WCMC

Models can help identify effective local policies

Assessing the impacts of concrete policies on biodiversity helps identify those policies most effective for safeguarding and promoting biodiversity and ecosystem services, according to the researchers.

The authors also note that even the most sustainable scenario assessed does not deploy all the policies that could be put in place to protect biodiversity in the coming decades. For instance, bioenergy deployment, one key component of the sustainability scenario, can contribute to mitigating climate change, but can simultaneously reduce species habitats. In contrast, measures to increase the effectiveness of protected areas or the regulation of deforestation were not explored in any of the scenarios.

The study clearly highlights that decisions made in one part of the world have multiple consequences – another reminder that policies shouldn’t take on problems in silos. We need politicians to consider how to deliver action under multilateral agreements holistically, keeping in mind the uneven historic and geographic distribution of the impacts of climate change.

There is also much more to learn: this work only studied trends and scenarios on land, but we know that what happens in the ocean has an enormous impact on land – and vice versa. It’s vital that we investigate interactions across realms further to inform the people who are making these important decisions.

Dr Samantha Hill, Principal Scientist at UNEP-WCMC

UNEP-WCMC is now working to adapt the global understanding produced by the research to local contexts. With the same group of researchers, Dr Hill is examining how local knowledge and values can be built into scenarios, so that the aspects of nature most valued by communities – for example, a charismatic species that is culturally important or valued for ecotourism, or a pollinating species that can help increase yields in agricultural areas – can be prioritised for protection and restoration.

Main image: Irrigated avocado and lemon orchards in California, US (Image: USDA Photo by Lance Cheung via FlickrPDM 1.0 DEED)

Have a query?

Contact us

communications@unep-wcmc.org