News

UNEP-WCMC scientists shed light on plant diversity ‘darkspots’ for major new report

News | Oct 2023

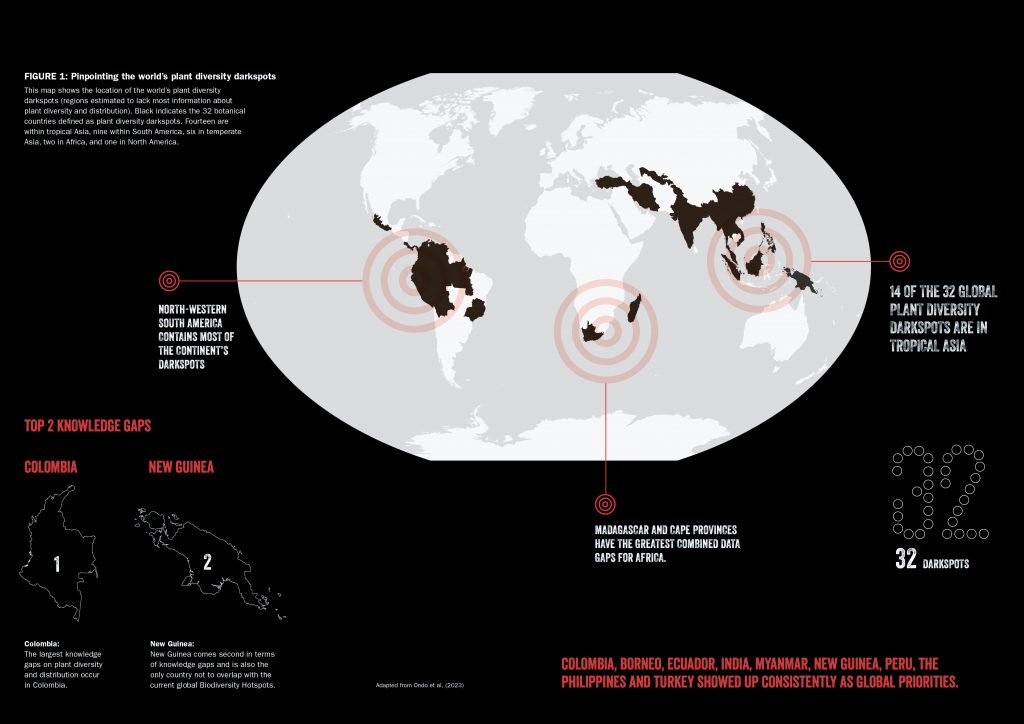

Scientists at the UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) have spearheaded new research identifying 32 global ‘darkspots’ where plant species are yet to be scientifically named, described and mapped.

There is a critical need to expand scientific knowledge of the world’s plants and fungi to help better understand the composition of ecosystems, their current and predicted responses to global change, and identify priority areas for conservation. A lack of data can lead to biased or incorrect scientific conclusions, and many of the new global targets for nature rely on having robust biodiversity data.

In an ambitious project undertaken by UNEP-WCMC in collaboration with scientists at Royal Botanic Gardens (RBG), Kew and other partners, researchers sought to shed light on the planet’s ‘biodiversity darkspots’ - areas where both geographic and taxonomic data are lacking, leaving scientists in the dark about their biodiversity.

The research forms a central chapter in Kew’s latest State of the World’s Plants and Fungi report, which has been published today. This year’s report focuses on what scientists do and do not know about the diversity of these fundamental building blocks of ecosystems, and estimates that 77 per cent of undescribed plants are threatened with extinction.

UNEP-WCMC scientists are the lead authors of a paper that provided the backbone for the chapter ‘Illuminating the darkspots of the plant world’. Their study modelled the number of species that are likely still unnamed and unmapped per ‘botanical country’ (countries or close equivalents). To do this, the researchers used the World Checklist of Vascular Plants, the Global Biodiversity Information Facility and other online resources to identify the plant species currently known to science, the year they were first scientifically described, and their patterns of distribution. Using these records, the team analysed historical and geographical patterns of describing and mapping plant species, and on this basis modelled how many are likely yet to be scientifically described and mapped.

They then examined where these darkspots coincided with the 36 recognised ‘biodiversity hotspots’ – regions of rich and unique flora that are also under threat – as well as how socio-political and environmental factors may impact botanical expeditions and guide future taxonomic efforts.

Findings highlight further research and conservation priorities

The study found that Colombia, the island of New Guinea and the region of South-Central China had the greatest global combined descriptive and geographical data shortfalls, in decreasing order.

Of the 32 darkspots of plant knowledge unveiled by the research:

- 14 were identified in parts of tropical Asia;

- Nine in South America;

- Six in temperate regions of Asia;

- Two in Africa;

- And one in North America.

The study aimed to address two major gaps in data related to biodiversity. The first is the gap between the number of species that exist and those formally described by scientists, while the second reflects the paucity of knowledge on the geographical distributions of species.

In the tropical Asia and South America regions, some countries were predicted to have taxonomic gaps of hundreds of species currently unknown to science, while Myanmar, the Indian state of Assam, Colombia and Vietnam were each estimated to have geographic gaps with missing data for more than 4,000 species.

The study found that the 32 darkspots broadly overlapped with the 36 biodiversity hotspots, with the notable exception of the island of New Guinea. While the island is exceptionally biodiverse it is still relatively untouched and therefore does not qualify as a hotspot (which must be both botanically diverse with high levels of endemism but also highly threatened); as knowledge gaps are filled and pressures increase this will likely change.

Resources to undertake new botanical expeditions or to digitise existing collections are limited, so we need to prioritise collection efforts. Knowing where there are most species remaining unnamed and unmapped, of which many are likely to be threatened, is crucial. Understanding where the unknowns are concentrated could also help us refine our estimates of priority areas for conservation.

Dr Samuel Pironon, Modelling Scientist at UNEP-WCMC and Research Leader at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

The shortfall in plant descriptions is substantial, with potentially tens of thousands of plant species yet to be scientifically named. We urgently need to address these shortfalls if we are to improve conservation plans and further develop effective actions to conserve, protect and value biodiversity.

Ian Ondo, lead modeller for the project, and Programme Officer at UNEP-WCMC and Senior Spatial Analyst at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

When the researchers assessed the influence of socio-political and environmental factors, different botanical countries and regions came into focus. For example, when prioritising botanical countries and regions with low-income levels, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Sudan and Angola became global priorities. Colombia, the island of Borneo, Ecuador, India, Myanmar, the island of New Guinea, Peru, the Philippines and Turkey showed up consistently as global priorities across all scenarios.

Many species that are not yet described by science are in fact well-known by Indigenous communities. And species extinctions and cultural extinctions are inextricably interlinked. With the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework highlighting the importance of Indigenous and local communities in conservation, we have the basis for strengthening partnerships and increasing our capacity to describe species in a way that can help raise conservation interest and funds to support local communities, as well as shedding light on darkspots.

Dr Kiran Dhanjal-Adams, Postdoctoral Researcher at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

RBG Kew’s fifth State of the World’s Plants and Fungi report lays out the current condition of the world’s plants and fungi globally. Based on the work of 200 international researchers and including more than 25 scientific papers, the new report examines global drivers and patterns of biodiversity as well as critical knowledge gaps and how to address them.

For one of the studies for the report, scientists analysed data from the World Checklist of Vascular Plants and the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species to examine links between the year a plant species is formally described and its extinction risk. They found a clear relationship between the year of description and the risk of extinction, with more than 77 per cent of species described in 2020 meeting the criteria to be assessed as threatened – an alarming finding given estimations that there are 100,000 plant species yet to be named. Based on these findings, Kew scientists are calling for all newly described species to be treated as though they have been assessed as threatened unless proven otherwise.

Main image: Adobe Stock

Have a query?

Contact us

communications@unep-wcmc.org